The “Poem Tree,” carved in England by Joseph Tubbs in the 1840s.

I apologize for the length of this post, my longest one yet. Sometimes it takes longer to examine what’s underneath an argument than to make one in the first place. As long as this post is, I kept it relatively short by focusing on this latest attack on Rita Dove’s anthology rather than Helen Vendler’s earlier one in the New York Review of Books. Dove very handily dealt with Vendler already and she chose to address primarily the racism and mischaracterization exhibited by Vendler, rather than another subject that Vendler veils even more than Perloff but one they both must see as another key culprit in the inclusion of the “many, rather than, few” poets: the MFA program and the presence of creative writers within the academy. Scholars have lost this battle, and creative writing is now well established in academia, so it seems that subject has sunk just below the surface. But it is never far below, and I believe we still need to address it directly.

Everybody Is a Poet

You know something is really wrong when someone mourns the success of a field she purports to love. Maybe love is the wrong word, so let me rephrase. You know something is really wrong when someone mourns the success of a field she has made her life’s work. The first line of Marjorie Perloff’s recent “Poetry on the Brink” in the Boston Review is “What happens to poetry when everybody is a poet?”

First, you would think that all lovers of literature and the arts would be jubilantly celebrating in the streets. I mean, my god, the novel may be dead, and support for the arts may be at an all-time low, but EVERYBODY has become a poet!!! How grand and unexpected an outcome is that?

But, no, according to Perloff, the popularity of poetry is a bad thing that ensures its mediocrity, or, as she puts it, “moderation and safety.”

Now, let me back up a minute. Is it true even that everybody is a poet these days? Obviously, in any literal sense of the word “everybody,” this is ridiculously untrue. Perloff bases her sense that everyone is now a poet on numbers provided in a lecture by poet and University of Georgia professor Jed Rasula: colleges and universities now employ 1,800 faculty in graduate programs, and that is only at the 177 graduate-degree-offering ones of the 458 institutions that teach creative writing, which “swells” the number of faculty teaching creative writing (now not just poetry) to 20,000. OMG, in a nation of 312 million, there are 20,000 employed teacher-writers. At least, thank god, their teaching keeps them busy a lot of the time, so they aren’t writing even more poems.

However, my next-door neighbors on either side don’t write poetry: the nurse, the retired engineer, the paralegal, and the fellow who owns a car dealership. None of them write poetry, and as far as I know, none of them read it either. When my undergraduates arrive in our introductory creative writing classrooms here at UCF, most of them have never read a poem by a living poet, and, though some of them may have written shortened lines of anguish in their online journals, or even in a notebook they keep under their pillows, they do not consider themselves poets. Their mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, and aunts don’t write poems, and the first time they venture to call some words they’ve written down a poem, they don’t feel safe at all. That is even more generally true for the F-school elementary students and the ex-cons and the nursing home residents that my friend Terry encounters in the Literary Arts Partnership she directs.

This is not to say that I don’t sometimes grow exhausted by the number of would-be writers I encounter in everyday life. Just about every week I do meet someone who wants to be a writer. The first I recall was a psychology professor who ran a fellowship program I was in during grad school—he became very insulted when I declined to read his novel manuscript. Then there was a stranger in a meditation class I took, who brought me rafts of poetry that I didn’t have the time or inclination to read. My hair dresser wants to write, as does the wife of a physician I worked with in the medical humanities. The Buddhist monk who ran the meditation retreat I attended a few weeks ago is working on a book. Every freaking doctor or nurse seems to want to write a book, except my next-door neighbor. (The plethora of medical writers is a post for another day.) At least once a semester, I get an email from a random person who has found my faculty website and who hopes that I will “edit” his or her manuscript for him or her for free, out of a “love of writing.” I don’t do it, but this is not out of any sense that none of these people has a story worth telling or a poem worth shaping. It is not out of a sense that they shouldn’t be trying to write. I celebrate their attempts, though it’s beyond my capacity to help them all, just as I imagine a doctor or a lawyer recognizes the legitimate health and legal concerns of many in the population without offering to treat or represent them all.

I’m also from a family of writers, some professional, some not, and I can say with certainty that the richness of that background has led me where I am today—not a famous writer, perhaps not even a particularly memorable one, but one who makes her living by the word. The many writers in my family—from my great-grandfather the journalist who published two books of natural history through my grandmother with her religious verses through my amateur-novelist parents (both of them!) and my long-time blogger brother—have not detracted from my own modest accomplishments, but made them possible.

Perhaps it is for that reason that I don’t think that a large number of poets in society is a bad thing, to the extent we even do have a large number of poets. I think, in fact, that it makes the likelihood of great poetry emerging out of the plethora of mediocrity all the greater. Even if most of the poetry today is basically compost, it creates a rich soil for a much wider possibility of poets.

I would like to point out, in fact, that even with the numbers that Rasula cites, we are talking about 0.0064% of the population making a living as writer-teachers. Hardly everybody, even if we trust his numbers, and I’m not sure if I trust the numbers of someone who equates 0.0064% with “everybody.”

That teeny-tiny percentage also includes writers who write primarily in genres other than poetry, but it doesn’t include the many published writers (especially those many in literary journalism and genre fiction) who don’t also support themselves by teaching. It isn’t those independent writers, however, that concern Perloff and Rasula, only writers who also try to survive the academic gauntlet and are thereby rendered “safe” and predictable as writers.

Note that Perloff is not arguing against the kinds of standards that she seems to think force creative writers in academia to become safe and mediocre. She is not suggesting that tenure for such writers in academia should be judged in some way other than the number of awards they’ve won or the number of poems they have published in journals any more than she is arguing that scholars of American literature should be judged by a standard other than the number of awards they’ve won or the number of articles they’ve published in academic journals, in spite of the fact that the readership of scholarly journals of criticism is lower and the percentage of work accepted also generally higher than in most creative writing journals. She is simply arguing that not so many of these writers should exist.

She is also not arguing that academia has produced a corrupted uniformity and mediocrity in literary criticism, which, if the logic holds, would also be the result of the tenure and publication process therein. Perhaps we should entertain the idea that all critics are dulled by academia and need to make their way as reviewers. There are certainly those in our state legislatures these days who aren’t sure that our public universities need so many of them.

Can you imagine a physician coming out with a public statement decrying the general population’s attempts to eat better or exercise or get vaccinations? Can you imagine a lawyer who would discourage folks from using an inexpensive online will-document or living-will service if they couldn’t afford a private attorney? Can you imagine a doctor noting that nurses are valueless just because they have R.N. degrees instead of M.D.s?

It strikes me as very strange indeed for someone like Marjorie Perloff—professor emerita at Stanford and the author of numerous books and articles from the academic press—to imply that the academic environment corrupts poetry. Jed Rasula, too—a full professor at the University of Georgia, whose publication career includes both scholarly work and a couple of books of small poetry from small presses—seems to have benefitted from the support of academia. (This is a point I will come back to later.)

The Ivory Tower, this one a castle built c. 1780s in Neath, Wales, and no doubt fought over until a ruin.

The Struggle Over Academic Territory

People, this is not about “everybody” becoming a writer. It’s a power-struggle over academic territory. Reading between the lines, what I find in Perloff’s lament are the following:

1) The idea that if you can’t be somewhere as illustrious as she is, then you shouldn’t be messing with poetry. If fewer people did it, then discussions of poetry would remain “lively and engaging debates about the nature of poetry and poetics,” as she thinks they were in the 1960s, even in the 1980s. (I don’t recall the former, of course, but the latter seems to me to have been just as full of territorialism.) Maybe it is okay to democratize engineering, but not poetry. It should still be an elite endeavor, protected from popularity and the masses of would-be writers.

2) The idea that the kind of poetry that Perloff promotes—“language” or “experimental” poetry—is the only truly innovative kind, even though that type of poetry is more linked to the institutions of learning that support it than any other kind. Though it is academia that she thinks supports a mediocre poetry, the poetry that has a better chance of popular success and survival outside of academia is, in fact, the “lyric” poetry that she finds so abhorrent. It is not Jed Rasula or even Charles Bernstein that sells poems outside of a narrow academic audience, but the likes of Billy Collins or, yes, Rita Dove, who comes in for such a beating from Perloff.

3) So, it’s not that Perloff doesn’t think there should be writers in academia or that academia should not support some writers. It’s that somehow academia isn’t only or primarily supporting the more “elite” kind of poetry that she supports—that is, poetry that has its roots in theory and intellectual ideas about language as opposed to what she considers banal imagery and feeling.

4) In other words, Perloff is doing what academics do, especially in times like these when resources are shrinking—she is conducting a turf war, an argument about what should be taught in the academy, and she is arguing for the styles she personally favors. Period.

The truth about this is that most (and I don’t mean all) “language” or “experimental” or “Conceptual” poets come out of a scholarly background. They came to writing via literary history and theory. There is absolutely nothing wrong with that, and most writers I know have nothing against the pursuit of this kind of writing by those drawn to it. However, the resentment that exists in English departments between the scholarly (PhD) people and the creative writer (MFA) types abounds. It always has. I guess, alas, it always will. The likes of Marjorie Perloff cannot be satisfied unless literary theory and intellectual debates about the nature of language come to dominate the creative writing parts of English departments. They do not see the success of creative writing (as it currently exists) as part of a shared success of the field of English studies, though I think they should, especially during times when many elements of our political world would like to eliminate the study of the humanities almost entirely. Instead, the rise of MFA and undergraduate creative writing programs threatens their hegemony and dominance.

The cover of one of my great-grandfather’s books, Rhymes, Roughly Rendered by T. J. Campbell, 1902.

The Place I Speak From

I feel I can legitimately speak to this because of my own liminality, not to mention my own lack of importance. I have an MFA in creative writing, and I have a PhD in American literature (a regular English PhD, not one with a creative-writing dissertation and a few extra lit courses). I even did one of my comprehensive exams on the subject of literary theory. I feel a great appreciation for and protectiveness of both of these veins of study, though it is true that my career has focused on creative writing. But you just don’t get MFA faculty attacking the very existence of the scholarly study of literature the way you get scholars attacking the creative writing endeavor. A few snide comments, sure, but mostly defensive ones. Occasionally these rise to invective, as in my former MFA mentor, the inestimable (and, for the record, entirely “experimental”) Paul West referring to scholars as “corpse-fuckers.” But nothing like the continual, in-print, organized, and elaborate attack on the existence of mere writers in the academy. Our muddling along as untheorized observers of the world, illuminators of the “small epiphany,” and explorers of intimate sensitivities is often (though thankfully not always) anathema to some (but thankfully not all) of our scholarly colleagues.

Trust me, I see many problems in the arena of academic creative writing. I am nauseated by the insularity of the prizes, the clubbyness of professional organizations, the back-scratching that so often is what leads to publication. I despair over the continued sexism and white dominance in spite of the “identity politics” that Perloff thinks produces only slight variation. (See, for example, evidence in the VIDA count and a recent report by Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting.) I could write expose after expose, rant after rant, bitch-fest after bitch-fest about the limits and bad advice that have been imposed on me and those I know within the tenure system, not to mention the disintegrating publishing industry.

Instead, I end up reading over and over again these disses against MFA programs, from within the academy, sometimes even from within MFA programs themselves..

I think of a conversation I had with my neurologist a few weeks ago, after it became clear that he had originally misdiagnosed a problem I was having. I like him—he had made the referral to the Mayo Clinic that finally resulted in a different diagnosis, because he recognized his own uncertainty, and he was modestly apologetic. “Sometimes,” he said, “I wish I were an orthopedist. I could say, ‘Oh, you have a broken bone.’ It’s clear and direct. Neurology is more complicated.” Maybe an orthopedist would disagree with this characterization, but seldom would one of these specialists be enough of a foolish ass to aver that the other kind shouldn’t exist.

Yet just that kind of thing is common in English departments and in online and print publications that are responsible for carrying on discussion of our literary culture.

The Adoration of the Magi by the Master of the Llangattock Epiphany from the 1450s, back when epiphanies could be large.

Perloff’s Complaints About Contemporary Poets

In this case, I find the following a selection of questionable assertions in the first half of Perloff’s essay:

* In Perloff’s outline of the three characteristics of contemporary poetry of which she disapproves, she notes “irregular lines of free verse, with little or no emphasis on the construction of the line itself.” This is an outlandish claim, and I know of no poets who think or teach little to nothing about lineation. How can she even say that? Of course, she bothers to give exactly no evidence or example. Free verse, of course, means that lineation must be constantly and individually attended to, not formulaic.

* She claims that another characteristic is “graphic imagery or even extravagant metaphor.” The adjectives here, of course, are simply a matter of taste and debate, so what she is objecting to is the foregrounding of imagery and metaphor in themselves, which are indeed key elements of most poetry. If one takes out the adjectives, one sees that Perloff must, then, be arguing against their use. Go ahead, I want to say, see where that gets you.

* What it gets us to is the third characteristic that Perloff dislikes, the “expression of a profound thought or small epiphany” that I mentioned before. Usually, Perloff notes, this is “based on a particular memory, designating the lyric speaker as a particularly sensitive person who really feels the pain, whether of our imperialist wars in the Middle East or of late capitalism or of some personal tragedy such as the death of a loved one.” I suppose Perloff would rather us celebrate or forget those things. At least, they are so trivial as to be beneath her. And it is here that Perloff really begins to show her own imperialist tendencies, but more on that in a minute.

* Perloff also claims that “[w]hereas scholars gain cultural capital as they move up the academic ladder and can—by the time they become full professors—feel relatively comfortable in their careers, poets are always being displaced by younger poets.” This statement made me laugh out loud. First, as so often with this article, I think that the fabric here contains only the thinnest thread of truth. If Marjorie Perloff doesn’t think she bears any threat from younger scholars, then she should be careful about how many times she hails the 1960s and the 1980s as a fabulously superior time to ours. Granted, perhaps it is so that youthful sexiness is more vaunted by the commercial publishing industry where creative writers hope to place their work than by the university presses that publish the scholars. Indeed, author photos do not hold the same sway in the scholarly world as in the creative. Indeed, even when a creative writer places a book with a large publisher, if sales are not meteoric, it may get harder to publish subsequent books, whereas scholarly presses accept a very modest definition of popularity and will often therefore continue to publish a scholar who is hardly a bestseller. But this is one thing that poets (as opposed to novelists and creative nonfiction writers) have in common with the scholarly writers—modest expectations of sales of books has led to long careers. Donald Hall, who Perloff mentions, for instance, has published 22 books of poems (plus numerous books of biography, short fiction, memoirs, and textbooks) since 1952, the most recent in 2011. Robert Pack has published 15 books of poetry and 6 of prose since 1955, with again the most recent in 2011. Perloff disproves her own remarks in this regard, perhaps out of some sense that poets should not ever become full professors. I hate to break it to her, but they do with regularity these days. If their publishing challenges are so much greater for them than the scholars, all the more reason to admire them.

* Perloff cites this insecurity in aging poets’ careers not as a lament, but as an excuse to note that they write the same basic thing over and over again in their books, that “somehow the fourth book, no better or worse than the previous ones, gets less attention.” “Ezra Pound’s ‘Make it New’ has come to refer,” Perloff sorrows, “not to a set of new poems, but to the poet who is known to have written them.” Ironies abound here.

Perhaps paramount is the utter repetitive nature of Marjorie Perloff’s work itself or that of almost any scholar in academia today, where we are trained not to be generalists (for better or for worse). Perloff has commented on an impressive array of modernist poets’ work and she has pounded in a variety of ways about the banality of lyric forms of poetry, but does her work really range more widely than that of most contemporary poets? Does her focus on the rhythmic and metrical, on the language aspects of modern and post-modern poetry really encompass that much wider a world view or strategy?

But, also, Perloff cites Ezra Pound’s “Make it New” as a rebuke to current poets for not being innovative enough and then goes on to note that statements about emerging hybrids between experimental and narrative poetry “don’t quite carry conviction” because “’an avant-garde mandate’ is one that defies the status quo and hence cannot incorporate it.” I know that Perloff has read Pound, and I am sure that she knows her Pound far better than I do. But we all also know that rebellion from the status quo and reverence for the forms and insights of the past were both key to Pound’s work. Perloff contrasts Whitman, Williams, and Ginsberg (those committed to “the emotional spectra of lived existence”) with Pound’s “collage mode.” So it seems to me that Perloff confounds two issues here: 1) age and tradition and 2) “feeling” versus “collage,” the latter meaning text sources of inspiration.

Any given poem and its construction beforehand is a struggle between all these forces or, perhaps, on a good day, a beautiful dance between them. This does not, as Perloff insists, mean that the choices are arbitrary or that they have nothing to do with the historical moment or the cultural context. Individually, they certainly do. But that does not mean that they cannot all coexist with the field of poetry or even within a single poet. It is not a war where there need be a battle to the death.

The cover of Rita Dove’s anthology.

The Meat: Perloff’s Complaints About Rita Dove’s Anthology

After this, Perloff gets to what it is that seems to have recently set her off: the publication of the new Penguin Anthology of 20th Century American Poetry, edited by Rita Dove. A long chastisement follows, in which Perloff takes issue with the omission of Random House poets that Dove and Penguin chose not to include because of prohibitive copyright costs. Dove has recently explained this decision in an AWP Writer’s Chronicle article, as well as in the introduction of the new anthology, but Perloff is not buying it and places the blame firmly on Penguin. “How,” she asks, “could a leading publisher such as Penguin fail to get publication rights for materials so central to a book’s purpose?” She does not mention that Dove has indeed explained this quite fully in print elsewhere.

Aside from whose fault the omissions are, this issue is a dodge that allows Perloff to critique the selections Dove has made, as well as her sense of literary history. Perloff claims that “one evidently wants to read her anthology not to learn about American poetry of the twentieth century but about her likes and dislikes.” In other words, Dove’s tastes are not adequate for the job, at least not in Perloff’s view, because Dove has not made the same selections that Perloff would have made.

At least not past the modernist era—Perloff notes that “however individual and intuitive Dove’s judgments on contemporary poetry, her Modernist canon… is more or less everybody’s Modernist canon.” Here is where Marjorie really begins to sound old. Here is where she returns to her earlier hint that she mourns the loss of a simpler time when everyone supposedly held a consensus about who the great poets were. She notes that before World War II everyone agreed on what the canon was. Alas, however, “the lack of consensus about the poetry of the postwar decades has led not, as one might have hoped, to a cheerful pluralism animated by noisy critical debate about the nature of lyric, but to the curious closure exemplified by the Dove anthology.”

Her lament about what Dove includes is then exemplified by Natasha Trethewey’s poem “Hot Combs.” Perhaps the oddest thing about Perloff’s reading of this poem is that, based on Trethewey’s own mixed-race heritage, Perloff assumes that the narrator of the poem is the poet herself. She complains that the poem, with its “easy conclusion that beauty is born of suffering, would seem to place this poem somewhere in the 1960s or ‘70s” but that it was published in 2000. Yet, Trethewey is known for combining her own personal experience with historical settings, including in her 2002 book Bellocq’s Ophelia, about a fictional prostitute living in the early 1900s. Perloff seems to willfully misread or oversimplify her reading of Trethewey’s poem.

But Perloff also makes another strange move here. She claims that “Hot Combs” exemplifies the three typical (and inadequate) characteristics she has noted above in the mediocre contemporary lyric poetry she is criticizing (no attention to line or word per se, prose syntax filled with imagery and metaphor, and the presence of a small epiphany. But only one of the the numbered list she gives in attacking this poem matches her list above in her second paragraph. Instead, she lists: 1) a present-time stimulus, 2) a memory, and 3) an epiphany (only this one matches). She does mention “prose syntax” and she insults Trethewey’s diction by putting “literary” in quotation marks before reciting a few of her descriptive phrases. But there is no coherence to the argument here. It’s just that Perloff doesn’t like this particular poem.

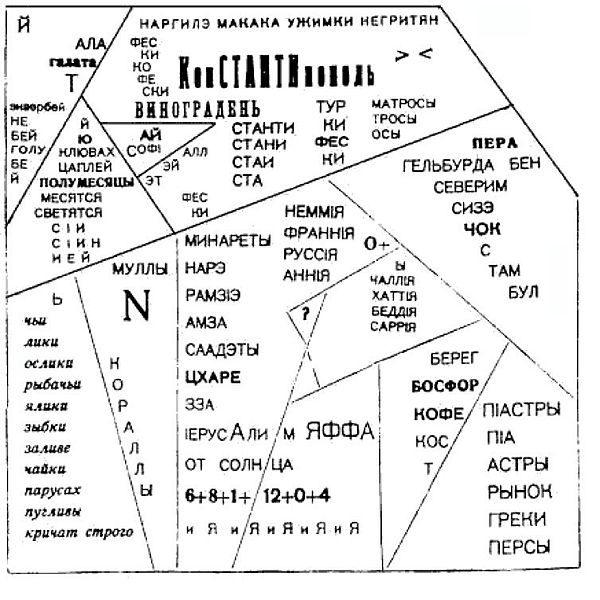

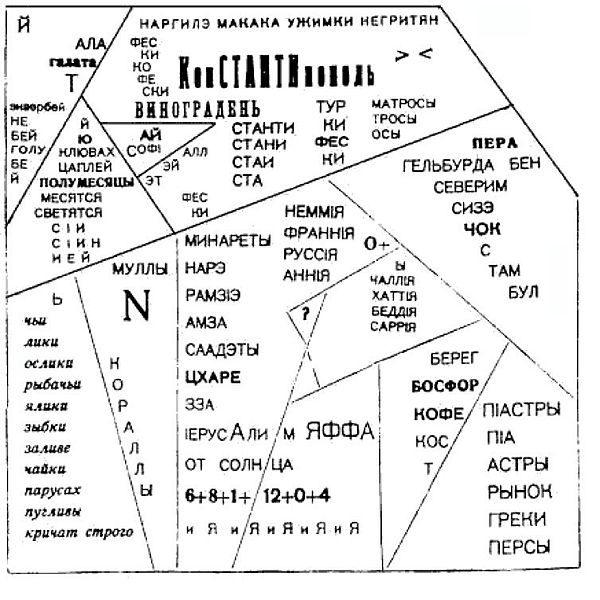

An example of “experimental” concrete poetry by Vasily Kameysky, 1914.

Perloff Turns to Supporting the Few

In the second half of her essay, Perloff goes on to write a manifesto about “a growing group of poets who are rejecting the status quo” with “what is now called Conceptualism.” The phrase “what is now called” seems to me to imply that she is simply talking about a different kind of status quo or tradition—in a direct line from the “language” and “experimental” poets of the past several decades. It also strikes me that somehow the fact that this is a “growing” group is used here to legitimize these poets, whereas the increasing size of the group of lyric poets somehow delegitimizes them. Go figure.

Perloff notes that the “main complaint against Conceptual writing is that the reliance on other people’s words negates the essence of lyric poetry.” She goes on to restate that Conceptual poetry is accused of having “no unique emotional input,” and that the question asked about it is, “If the words used are not my own, how can I convey the true voice of feeling unique to lyric?” As usual, Perloff doesn’t cite any examples of this argument, and perhaps it is true that some people have said this kind of thing. But most poets, even the lyric poets that Perloff seems to think are utterly stupid, are not that naïve. They don’t claim that the words they use have never been used before, and they often pay homage to other poets in their work. In fact, they often themselves produce mash-ups, and many of the literary magazines that Perloff suggest contribute to a uniform mediocrity send out calls for poems that do just that (For instance, here’s one from Crazyhorse: Cross-Off Contest). It is part of the conversation that is literature, no matter the style.

Perloff then asserts that the musicality used by John Cage in his re-working of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl is “absent in most contemporary poetry,” a slam that literally stuns me. She chooses one example “at random” (I doubt it) that she then turns into prose and notes that Cage’s poem “cannot be turned into prose” because of its “very formatting.” Well, really, I could turn it into prose, but, given that the Cage lines are further from usual prose syntax than the lines she quotes from Dove’s anthology, is Perloff really suggesting that prose can have no musicality? And has she read the same contemporary poetry that I have? Plenty of it is musical and rhythmic, and if some of it is less so, why should poetry have to conform to a formula of musicality any more than a formula of tripartite “observation—triggering memory—insight” or the 14-line form of a sonnet?

For example, these few lines from “The Golden Shovel,” written by a young poet I’ve recently discovered, Terrance Hayes:

When I am so small Da’s sock covers my arm, we

cruise at twilight until we find the place the real

men lean, bloodshot and translucent with cool.

His smile is a gold-plated incantation as we

drift by women on bar stools, with nothing left

in them but approachlessness. This is a school

I do not know yet. But the cue sticks mean we

are rubbed by light, smooth as wood, the lurk

of smoke thinned to song. We won’t be out late.

Standing in the middle of the street last night we

watched the moonlit lawns and a neighbor strike

his son in the face. A shadow knocked straight.

[from Lighthead, Penguin, 2010]

To describe this work, and work like it, as having no musicality requires an unimaginably deaf ear. I know Marjorie Perloff cannot have such a deaf ear. So why does she make such an enormous, vague, insupportable claim? She seems to me to be grasping at some kind of legitimacy for poetry she feels is unappreciated, and she goes on to analyze the work of four poets she likes.

Death is a common subject in many styles: The Death of Henry VII represented in a medieval miniature.

Perloff’s Four Poets

First, she discusses That This by Susan Howe, who she notes was not included in Dove’s anthology but who nonetheless “would not call herself a Conceptual poet.” In addition, Howe’s book focuses on the sudden death of Howe’s husband, Peter Hare, that subject matter of “personal tragedy” that Perloff earlier criticized in lyric poetry. The difference is that Howe reconstructs her poems out of fragments from other sources.

Don’t get me wrong—Howe’s work sounds fascinating to me, and I fully plan on looking it up. Perloff is at her best when she writes passionately in support of work that she finds interesting. She convinces me that Howe’s work is worth a look.

* Likewise with another set of poems that Perloff analyzes in some depth—from another poet she characterizes as “not primarily a Conceptualist”—Srikanth Reddy’s re-working of the memoirs of former Nazi and president of Austria Kurt Waldheim into a work Reddy calls Voyager. And again Reddy seems to partake of a subject matter that Perloff has criticized—sensitivity of feeling about “our imperialist wars.” Reddy’s work is different not just because he has re-worked an earlier source, but because his poems are “free of all moralizing or invective on the poet’s part.” I understand that there are shades here, but I am not sure how Reddy’s “critique” of Waldheim’s hypocrisy and of “political mendacity in general” is free of moralizing. His project and its outcomes seem inherently (and appropriately) moralizing to me.

Both of these books also sounds as though they need to be seen in their entireties—in book form—to be fully understood and appreciated, something that it’s difficult to present in an anthology. Perloff even says this herself: “Like Howe’s” book, Reddy’s “has to be understood as a poetic book rather than a book of individual poems.” How, then, would she suggest that Dove anthologize them?

* Recognizing this issue, Perloff then turns to recent short work by Charles Bernstein. Bernstein, she notes, has been criticized for becoming “easier” in his more recent work, but she argues that the trickiness of assessing Bernstein’s tone in such lines as the following renders his work still compelling:

No, never, I’ll never stop loving you

Not till my heart beats its last

And even then in my words and my songs

I will love you all over again

Bernstein, Perloff notes, is posing the question of “how to come to terms with this embarrassing bathos.” That makes the bathos interesting, though, of course, it is not an excuse that is allowed the “status quo” poets that she criticizes.

* Perloff’s last example of a poet she deems worthy is Peter Gizzi, who has written a collection called Threshold Songs “in response to a series of deaths—his mother’s, his brother’s, one of his closest friends—so overwhelming they can hardly be processed.” Again, because it “avoids the unsayable by its appropriation of other voices,” Perloff believes that Gizzi has written a more legitimate series of poems about his own personal tragedies than people who write more directly from their experience.

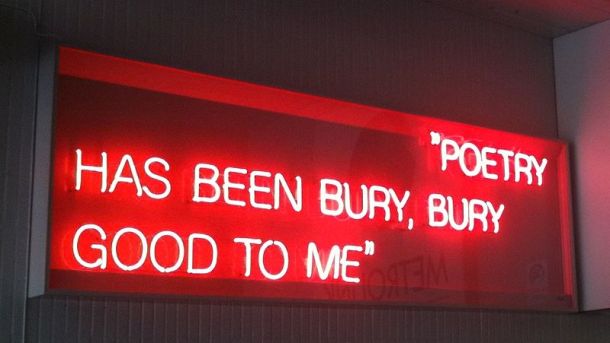

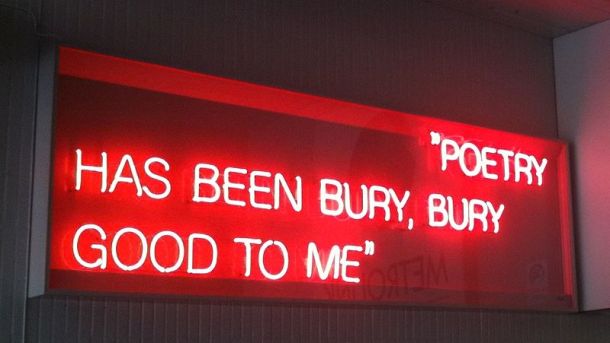

Ron Stillman’s neon sculpture “From Northern Soul (Bury Neon),” Greater Manchester, England, 2011.

Concluding the Inconclusive

Perloff ends her essay rather suddenly by noting that, “Increasingly, the ‘true voice of feeling’ is the one you discover with an inspired, if sometimes accidental click.”

Honestly, I don’t even know what she means by this last statement. Does she mean poets themselves or readers of poetry? And, while I guess she’s been making the case for a particular mash-up strategy of writing, she seems to have lost the point of arguing against the tradition of lyric poetry. Surely, she doesn’t mean that the only legitimate way to write poetry is to re-write other texts?

And for someone who is here to champion hard-core experimental and Conceptual work, Perloff has now given us examples from two people who don’t consider themselves Conceptualists and two examples of Conceptualists, one who has softened the Conceptual line around his work, and another who has taken up the lyric subject of his own personal tragedy. Does she really believe, then, that hybridity is impossible and an unconvincing storyline as she asserted early in the essay when she briefly mentioned Cole Swensen and David St. John’s anthology, American Hybrid? Her own examples seem to me to prove its healthy existence.

I do, however, agree that, as Perloff states early on, “Formal choices are never without ideological implications.” I believe that Perloff’s choices certainly have them, and that her ideology most clearly supports an elite of the elite. Writers and readers of poetry are quite an elite all on their own, and when you sift out the grandmother-amateur-poets, they are even moreso. But Perloff seems to me determined that poetry will also remain shuttered from lived experience, centered in the halls of intellectual academe, and upper crust, if not essentially white and male (Reddy, of Indian descent, attended Harvard and the University of Iowa). She does not celebrate the vernacular found in poetry she would call unmusical, nor in the actual experience of loss or suffering, only in sublimated versions. A poetry based in the middle class or the working class must be anathema to her, just as any but the most intellectualized ideas about poetry are.

I want to make clear that I do not think that debates about quality are not relevant or appropriate. But what I see in Perloff’s essay is fundamentally a grasping to preserve the values of a time long past—a pre-World War II era when scholars defined quality, when poets themselves were largely excluded from the academy, before they had infiltrated it in creative writing programs and had begun to find the platform to assert their own definitions of quality that were often at odds with their more theoretical scholarly colleagues. Perloff notes indignantly that Rita Dove’s anthology “depends not on … its capacity to satisfyingly delineate a poetic canon or make some claim about the nature of poetry in a certain time or place—but on the prestige of its editor.” It seems outrageous to her that Dove is “prestigious” in spite of her 13 books.

It is entirely possible that Dove has made selections for this anthology based more on a creative writing sensibility and pedagogy than that of a scholarly literary one. Indeed, the delineation of a canon or the examination of the cultural and historical aspects of poetry is often not the focus in creative writing courses, though creative writing students are always required to take numerous literature courses in which they are. It is also true that creative writing pedagogy and traditions often function with a more idiosyncratic and artisanal model of teaching and learning than do scholarly ones. Perloff clearly believes that this is wrong-headed, as do many in the scholarly literary field, and she insults these methods by stating that she wonders if the intended audience of Dove’s anthology is “junior high students.” It is true that creative writing pedagogy in the wrong hands can be too easy and indulgent, but in the right ones it can be rigorously powerful and empowering. There are many variables that contribute to particular outcomes. I just wish that Perloff would admit that what she is doing is longing for a time before creative writers per se had a place at the table of deciding what poetry has merit. She wishes it were only the scholars and the few scholar-poets who had the kind of “prestige” that Dove now shares.

If Dove has constructed an anthology suited to her own reading and teaching preferences, what is wrong with that? Is it not the same method that Perloff herself uses when she edits anthologies and decides what works she will include on syllabi? As Rasula notes, in academia, we are trained to be “specialists,” and Perloff herself is not asked to teach courses in the Victorian novel. I can fairly safely assume that she has never included a Rita Dove poem on her syllabus in spite of the fact that Dove has published more books and has been more widely read than some of the post-modernist poets that Perloff favors. It is probably true that most poets teaching in academia weight their teaching toward the lyric, and even poets in that tradition (such as Carolyn Forché) have worked to open it beyond the personal to a more political consciousness. But these poets have asked that the door be opened, not that another door be closed.

The second half of Perloff’s essay, though not particularly logically consistent, nonetheless serves a valuable purpose: supporting four poets whose work she finds compelling. I am all for that.

Yet I must point out that Peter Gizzi is a full professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Charles Bernstein a named professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania, Srikanth Reddy an assistant professor of English at the University of Chicago, and Susan Howe retired as a named chair at the University of Buffalo (formerly SUNY Buffalo). Of the four poets that she mentions early on that she feels were neglected in Dove’s anthology—Harryette Mullen, Will Alexander, C. S. Giscombe, and John Yau—all but one has a full professorship at a prestigious university, and even the one (Alexander) has taught in several places while making the choice to remain in his native L.A. All of them, in spite of some of their and Perloff’s protests, have successful careers legitimized within the very academy Perloff wants to blame otherwise for the mediocrity of contemporary poetry. They are all also writers whose work is deeply connected to the scholarly, theoretical, and historical tradition.

Academic historians and theoreticians of music and the visual arts can’t so easily cast out the practitioners of music and art—their media require a different kind of technical facility than the scholars have. But when the medium of art is language, too often the scholars don’t believe they need anyone but themselves.

And this turns me again back to the first half of Perloff’s essay, which seems to me an unacceptable diatribe about MFA programs in creative writing and the influence of academia on poetry, that is, on poets within academia who do not toe her rarefied intellectual line. I do believe that we can debate the merits of specific poems—and the Trethewey poem that Perloff critiques will likely never be one of my favorites. I agree that we can debate what the most important elements are in poetry, too. But this kind of hand-waving, overgeneralized dismissal of MFA programs and lyric poetry is less than we deserve from our well-known public intellectuals in the field. I am a relative nobody, with no doubt a less lofty education and certainly fewer credentials on which to stand than Perloff and her Harvard and Berkeley cronies, and even I can think beyond this.

We need to celebrate in the streets—and in print–the rise of creative writing’s popularity in the public imagination and in our colleges and universities, or else we really could end up dancing on the grave of poetry one day soon. Just about 99.9936% of the population may not even notice.