You might not think that the Penn State child abuse scandal and Occupy Wall Street have much in common. But maybe I can explain why I will celebrate OWS every day until they are smashed completely by those who don’t want to hear it. It’s not just because they have a point, but also that they are willing to make it.

I spent 14 years in State College, Pennsylvania, first working at Penn State and then earning two graduate degrees there. I never met Jerry Sandusky, met Joe Paterno only once briefly, and only met Graham Spanier a handful of times, though I worked for his wife as a research assistant for a year and sometimes filed papers in their presidential home.

In spite of many claims circulating these days, a devotion to football is not required for membership in the Penn State community. I attended one football game in all my years there, and I left at half time, though I was sitting on the fifty-yard line in the company of a member of the Board of Trustees who was much older and more important than me. This latter was a situation chock full of a low-level sexual harassment that I managed to deflect, but I remember how it felt to say no to a person vastly more powerful than me. Maybe those connections cause me to want to comment on the recent scandal, or maybe it’s just my status as a human being.

Certainly the internet has been lit up with outrage about Jerry Sandusky’s behavior and about possible cover-ups that occurred in the Penn State football program and beyond. I participate fully in some of this outrage—we should assuredly feel it when any child (or adult, for that matter) is sexually assaulted —much less numerous ones over years. Certainly we should expect that all people who witness such a situation, directly or indirectly, should find it worth their trouble to do all in their power to stop it.

But when we expect the latter, we are hoping for people to break an ingrained habit that we usually approve of and take for granted in other situations, a habit that is generally rewarded. Granted, a crime, particularly of a heinous nature, should call for the setting aside of politeness and self-interest. But why is it that so often it doesn’t?

When, in fact, was the last time that you or I looked the other way and didn’t speak up in the face of an injustice, wrong, or lie? Probably yesterday if not today. So I agree that much with neoconservative columnist David Brooks’s recent opinion. I don’t, however, believe it’s because we’re all just inevitably sinful. As Daily Kos blogger Frederick Clarkson pointed out, that’s a dodge. Instead, I believe that, especially in many of our places of employment, we are trained in an anti-democratic obedience that is a hard habit to break. It takes a lot to rehabilitate Pitt bulls that are trained to fight; most humane associations euthanize them rather than ever expect them to recover. Like Pitt bulls trained to fight, people trained to be yes-men and yes-women have a hard time overcoming the pattern.

I also agree with much of what Michael Berube said recently in the New York Times about the Paternos’ academic heritage remaining intact. I wonder, however, whether greater faculty involvement in the governance of Penn State would have made a huge difference, as he claims. Faculty are not fundamentally different from anyone else, and they are no strangers to politics that favor yes-men and yes-women. Faculty are no strangers to pumping up numbers for the image of a program when the reality is not so keen. Faculty are no strangers to unfair practices, and many faculty have never spoken out about even the less drastic (and less risky-to-reveal) wrongs they might witness in their daily work. What Berube suggests would only help this kind of situation if it were one in which faculty themselves did not have to fear repercussions from those more powerful than they.

This is by no means exclusive to universities with football programs. Even though laws that protect them somewhat have been on the rise since the late 1980s, whistleblowers from all walks of life report the high price they often have to pay for their honesty, even when the behavior they report is criminal. (Just type “whistleblowers pay a price” into Google for 2,960,000 hits. Or read this other New York Times column by Alina Tugend who traces psychological research into why this is.) People lose their jobs, entire careers, their marriages, their homes, sometimes even end up on welfare waiting for cases to be resolved. Even in a best case scenario, people who blow the whistle look forward to years of punishment.

There’s another complication here as well, and I finally figured this one out after reading Sara Ganim’s Patriot-News account of conflicting testimony about reported incidents with Sandusky. The article does a great job of laying out all the different indications there were that something seriously wrong was going on. Yet, I didn’t quite agree with its last statement that, “everyone cannot be telling the truth.”

What the litany of reports reminded me of was the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986 and the reports by the Rogers Commission that came out afterward analyzing how on earth NASA could have launched a mission with a combination of factors almost certain to bring the ship down and kill its seven crew members.

When I was a graduate teaching assistant at Penn State, in fact, we used the Space Shuttle Challenger as a prime example in composition classes of why clear and honest communication is important. We used it as a case study of how communication can go wrong. Engineers knew that the Challenger was likely to fail, but the authoritarian culture of NASA and the media pressure due to the inclusion of schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe on the flight made those engineers afraid to assert what they knew in no uncertain terms. As the warnings went up the chain of command, they were repeatedly weakened until they became completely vague euphemisms that did not indicate the extent of the danger. Thus, the fatal decision to launch in spite of low temperatures for which the O-rings had never been tested and were unable to hold.

Here’s how the evolution happened at Penn State, as well laid out by the Patriot-News article:

McQueary: anal rape.

Paterno: something of a sexual nature.

Schultz: inappropriately grabbing of the young boy’s genitals.

Curley: inappropriate conduct or horsing around.

Spanier: conduct that made someone uncomfortable.

Raykovitz: a ban on bringing kids to the locker room.

It’s like a game of Telephone, only the scrambling isn’t random; rather, the message remains coherent, just weaker and weaker.

It is also, Tracy Clark-Flory notes on Alternet (originally Salon), very common for child sexual abuse to be overlooked, ignored, or covered up. By no means are McQueary, Curley, Schultz, Paterno, and Spanier alone in their inability or unwillingness to face up to what was going on.

None of that excuses what happened at Penn State, either the abuse perpetrated by Sandusky or the failure to stop it by others. It does, however, make surprise about it somewhat disingenuous.

And, in spite of my disagreement with David Brooks’s “original sin” kind of thinking, it also means that one of the many places we should look in the aftermath is within ourselves. We can hope that each of us would have the decency to stop and report far and wide such events and suffer the counter-accusations, the damage or complete destruction of our own careers, and the necessarily long, perhaps public, involvement in attempts to rectify something dirty and disturbing. I hope for myself personally that I would have the nerve, and I think I would. Still, while most of us may not be sick or criminal in the vein of Sandusky, we are a lot more like the others than we would like to admit.

So it disturbs me that most of the “attempts to heal” that I’ve seen focus on this false question, “How could it happen?” rather than “How can I prepare myself never to fail in this way?” Externalizing all the blame is inappropriate. We need instead to create different habits in ourselves: habits of telling the truth and speaking out.

Even when we have perfectly good reasons for speaking out, we may be discouraged from doing so. There are kinds of damage less than losing an entire career. There is damage that isn’t even as clear as pepper spray in the face of a protester.

I myself was told by an administrator at my university that in order to make my way in the face of certain manipulative and back-stabbing behavior I just need to get more “strategic” myself. I told him I would rather fail completely than become devious and dishonest. And there’s a very good chance that I will fail by a certain set of standards. In some ways I already have.

Recently a colleague of mine in another place has been sidelined from a program she developed precisely because she criticized the performance of a senior-level administrator for some serious errors. Now an additional faculty member has been added to help further the program and, now that there’s potentially someone else to run it, that senior administrator is saying that she won’t approve of the next phase (investing the resources to create an international center likely to have some renown) unless my colleague be excluded from having anything to do with the program she created. All because the administrator doesn’t like this person.

I also have an acquaintance who was sexually assaulted by an employee of the college where she worked. Because there was no “proof” the institution refused to act on her complaint, and her colleagues wanted her to shut up about it so as not to damage the institution’s reputation. She became—in my eyes, undeservedly—a pariah and eventually left for another, lesser job.

None of these situations is as clear as the issue of speaking out about a child being raped, of course. But I do believe that those of us who are in the habit of speaking out about lesser wrongs are more likely to speak out about greater wrongs. We know how to bear the anger. Some know how to withstand the pepper spray and tear gas.

The trouble is, of course, that it’s very hard to tell the difference between a truth-teller and a mere trouble-maker or even an asshole. For those of us who are not complete corporate or university sell-outs—yes-men and -women who have consciously prioritized getting ahead—the main quandary is how to create the habits in ourselves of telling the truth without becoming simply obnoxious.

We all know the types that everyone avoids, whose sense of what is wrong in the world may be paranoid or self-serving or just plain crazy. We know the ones who are just angry all the time and who will lash out at anyone with an accusation.

In order to try to prevent my own corruption in this regard, I have to always remember that other people see things differently and have a perfect right to do so, that I should say what I think but be ready for the (sometimes legitimate) push-back, and that I will never, ever be popular. Even accepting all that is no guarantee I won’t end up either fudging the truth sometime to get ahead or obsessing about something others see differently. All of us can only try to remain aware.

Beyond myself, I grieve a societal structure that is based to such an extent on a false meritocracy. The belief that greatness necessarily rises to the top poisons a lot of our professional interactions. This, too, is a difficult issue for me. As a teacher, I do indeed want my students to grant me the respect and authority accorded by my education and experience. Fundamentally, though, I don’t want anyone to think they are ultimately inferior or superior to me. I squirm within a university hierarchy in which individuals are expected to show constant deference to those in higher positions and where any questioning, no matter how polite, is considered disrespectful.

Hierarchies are based in the idea that some people are superior to others. This should be in a limited and role-based way at best. But too often, the skinny woman just thinks she’s a better person than the fat one. Too often, people believe that the wealthy deserve it. Too often, the boss sees himself as having a God-ordained entitlement. And in situations like the one in which Michael McQueary witnessed his “superior” doing something terrible, he responded with the assumption that others were in charge, others were responsible, others knew better than he did. We are asked to respond this way almost all the time.

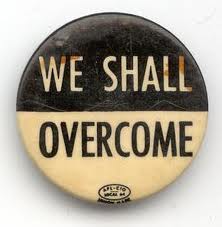

On the other hand, I have in my mind’s eye an image of Myles Horton, one of the co-founders of the Highlander Folk School in East Tennessee that became a training ground for labor and Civil Rights leaders in the 1940s and continues social justice work today. Horton came to speak at my undergrad institution in Minnesota one spring in the early 1980s, an old man who still had a lot to say. I was dating a boy who was interested in Horton’s politics, but I went to see him partly because I was homesick for the gentle rising East Tennessee spring while I sat in a snowbound Minnesota April. He kindly spoke to me about the mud and the unfurling of the bright green, baby leaves and the redbud blossoms, and then he turned to the larger audience and announced, “Democracy is not efficient.”

There is a way of thinking about democracy that means “equal opportunity” to scramble to the “top” with those at the top necessarily defined as deserving. And there is another way to think about democracy, which is that no matter where on the ladder one is, one is an equal as a human being and has rights. Though there is no party or political persuasion that is without its spin, euphemism, power dynamics, even sexual misconduct, I lean left because I think the left’s vision of democracy is closer to the latter than the former definition.

No, democracy is not efficient. If all the managers, administrators, and bosses in the world had to listen and respect others, it might be a boatload of extra work for them. I watch, in fact, as my husband tries to chair a department this way, and it’s hard. He comes home exhausted by the sometimes heated arguments of his department members. I always tell him that they are truly better off because people are willing to put it out there, in contrast to my own department, where it is all under the surface and uglier for it. So, that’s not an easy prospect. But deep and abiding democratic values, practiced daily, might be the best bet against silences that harm and kill.