I like my decaf coffee as strong as any caffeine-lover.

I’m about to offend some of you addicts: coffee addicts in particular. I put it this way because what I want to say is that caffeine is a drug, and it’s a drug whose consequences are mightily ignored. I had reason to contemplate this fact yesterday because I went into a coffee shop.

The man behind the counter was about my age—the hair drawn back into a pony tail had grayed, and wrinkles crisscrossed his forehead and cheeks. When I entered through the back door (from the parking lot), he was seated at a large sink washing plates. He looked up sideways at me, but didn’t move. The recognition that passed over his face wasn’t real recognition, just typing. Immediately, I could see he didn’t like me.

Mind you, I had never been in this coffee shop before. I knew of it from my students, who sometimes spoke of its open-mic nights and artsy vibe. The only reason I had stopped there was because it sat directly between the hardware store, where I had gone to buy some plant potting supplies after my haircut appointment, and the hospital medical plaza, where I was due in an hour for an MRI, another MRI.

While I stood waiting, I glanced around the dingy interior. A young man sat behind me at a table, tapping into his laptop, a knit cap pulled down over his head in spite of the 85-degree day. A young couple sat holding hands on one of the sofas in the open area up front, a laptop on the coffee table in front of them, their intensity focused between the three of them. In an upholstered chair, another young man sat with his back to the counter; I couldn’t see his face, but he, too, was young and seemed to be reading, his hair sticking up with gel around his cranium as though very excited about the ideas he encountered. But he slumped in the chair, one leg thrust out as though barely able to hold him up. Bright mid-afternoon light streamed through the front windows, picking up every crumb and smear on the filthy floor. I didn’t mind. I have worked in many a dirty restaurant in the past. All I wanted was a peaceful place to pass half an hour or so, reading the book I’d brought along for this very possibility of a time gap.

Finally, the aging hipster stood up, wiped his hands across his apron and asked me, “What can I get you?”

“A medium decaf latte, with skim if you have it,” I said.

He moved over to the espresso machine. “What size?”

“Medium,” I said. I liked that Austin’s menu board used small, medium, and large instead of the deceptive and silly tall, grande, and venti.

“You said decaf, right?”

“Yes,” I said, and then because the barista response is so predictable, I tried to make light of my request. “You don’t want to see me on caffeine.” I wiggled my fingers in the air.

He did not smile. Sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t. But I was starting to get worried. I mean, I was the brain patient, and my short-term memory seemed better than his.

“What kind of milk do you want? We have whole, half and half, two percent, soy, and skim.”

“Skim is good,” I said.

I tried not to stare as he moved around the space, tamping the coffee and turning the levers, so I looked back out the front window as a kid wheeled off on a bicycle. When I turned back, the guy was putting the whole milk back in the fridge. I decided to let it go.

Then he asked if I wanted whipped cream. A little surprised—since when is whipped cream part of a latte?—I shook my head and said no emphatically. He poured the last of the milk with its top of foam into the cup, then lifted a plastic bottle and squirted Hershey’s chocolate syrup all over the top before I could say a word. Who puts chocolate syrup on a latte? My god, I thought, he must have a lot of those little girl customers to whom coffee drink means sugar drink.

I gave the man my five-dollar bill, then transferred the change into his huge and stuffed tip jar. Briefly I contemplated the ridiculousness of this current coffee fad. We’ve all gotten used to the idea that these large sums are worth it to get exactly what we want in a cup of coffee.

However, I at least seldom get exactly what I want in a cup of coffee at a coffee shop, and I am vowing now to give it up pretty much entirely. If I have to meet someone at a coffee shop, I will order something else. Because I am very tired of baristas giving me caffeinated coffee when I order decaf. And I am tired of the attitude that also sometimes comes with such a request. Still, I would rather have the put-down attitude and get my decaf than have the silent but disobedient person who chuckles as he gives me a drug that my body cannot handle.

One barista even asked me once why I bothered if I was going to have decaf. Usually I am mild in my response—after all, these people have my coffee in their hands—but what I always want to say is, “Can’t you see that the person who orders decaf is the one that really loves coffee? All I want it for is the flavor. You caffeine drinkers are simply using it as a vehicle for your stimulant. Why not just take it in a pill if that’s your motivation for drinking coffee?”

I am a genuine coffee lover. I love the smell of it, I love the taste of it, the darker the better. Unless I drink the occasional latte, I drink it black as I can get it. I seek out French roast or at least Italian when buying it for home use, though it can be hard to find. I virtually never add sugar to it.

Yet, over and over and over and over, these macho little baristas (who are indeed always skinny) turn up their twitchy noses and their stubbled chins at me, and treat me like I’m some sort of inferior being for asking for decaf.

Maybe they find an excuse to treat every mature person this way. I forgive them over and over and over again for being young. I was young once myself, and in my waitressing days, there were numerous times when I would pour a decaf refill from the regular pot. But I only did it in an emergency—when the decaf pot had run dry. True, I didn’t fully understand the importance of the request, but I never sneered. Still, sometimes I tell myself that every time I get a cup of caffeinated coffee it’s just karmic justice. But I’ve paid those dues enough now, and I’m over it. And there’s no excuse for a middle-aged barista acting this way. The coffee world has supposedly opened up in the past decade, and the idea is that there’s a wider variety available and more understanding about coffee.

However, no one wants to hear much about the destructive nature of caffeine or admit it by providing someone a decaf. Smokers love smokers, and caffeine junkies love caffeine junkies. Mind you, I have nothing against caffeine junkies—unlike smokers, their addiction doesn’t waft over into my nostrils. Unlike over-drinkers, they don’t wreck cars and kill people.

Or maybe they do. We’re all familiar with the upside of caffeine consumption—the alertness and fatigue-fighting aspects that seem to apply to both cognition and physical activity. But there are downsides, too. The Mayo Clinic website reports that in addition to the usual side-effects of insomnia, nervousness, restlessness, and irritability, more than 500-600 milligrams of caffeine (about two Starbucks tall coffees) a day can produce stomach problems, fast heartbeat, and muscle tremors. Jack James of the National University of Ireland, Galway, notes (about halfway through this interview) that blood pressure changes from caffeine consumption may be a major factor in cardiovascular disease. A whole host of studies note the bad along with the good in caffeine consumption:

* Good news, bad news

* Fitness benefits and risks

* Be cautious

* Negative may outweigh any positive

* Cognitive impact is mixed

You’ll note that all of these studies rely on an understanding of how much caffeine is consumed, and if you’re curious for yourself, here are some tools for gauging your own intake:

* The Caffeine Database

* Center for Science in the Public Interest caffeine chart

* Starbucks caffeine information

Of course, as with any drug, people’s reactions to caffeine vary enormously based on an individual’s sensitivity. Caffeine is associated with panic attacks, and studies have clearly shown this association, especially for those prone to panic attacks or major depression. But even some in healthy control groups reacted to caffeine with panic attacks or anxiety, whereas none did without caffeine.

And, though not prone to panic attacks or major depression, I’m one of those people who is sensitive to caffeine. Even one cup can make my hands shake and, later, will most assuredly keep me awake all night, no matter how exhausted and strung out I am. This is what happened to me yesterday.

I sat down with my cuppa in Austin’s and opened my book in pleasurable anticipation of my hour of reading. The music blaring from the speakers distracted me a little, but again I felt good-humored about the off-key adenoidal voice, amateurish strumming, and angry-young-man lyrics. “Everyone is interesting but you,” sang the adolescent, who then spat out several expletives. I decided it was the nastiest acoustic music I had ever heard, and it amused me no end that this placid coffee house in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods of Orlando ebbed and flowed with such anger. It went on song after song, and I wondered if the recording featured some local singer, or even the barista himself. It was so bad I had to wonder.

My lack of suitability for this place also flowed over me with the music. I was too old, had no tattoos or body piercings, and was wearing light-colored cotton and sandals. My difference didn’t really matter to me, but soon enough I would think it merited punishment from the coffee tsar. I sat back and turned the pages in my book.

Then my fingers started to feel a little panicky.

Now, an MRI is not an experience to relish. Before yesterday, I’d already had two in the previous 16 months, and I wasn’t really looking forward to another hour in the noise chamber with my head in the tight frame and my eyes shut to prevent claustrophobia, trying to keep my mind busy with thoughts of words, and glasses of wine, and the smell of jasmine on the breeze. So I thought I was just getting nervous about that. Eventually I closed up my book, tossed the cup with its last bit of chocolate syrup and milk foam in the trash, and headed for the hospital, leaving the grunge scene behind.

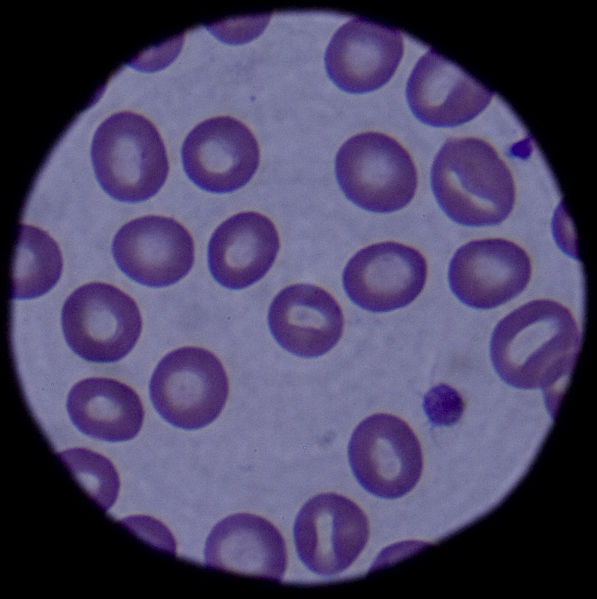

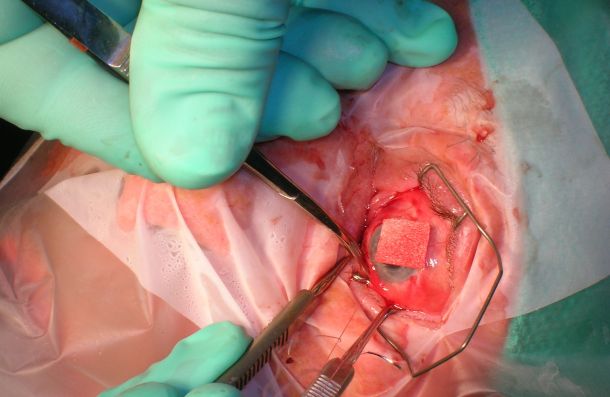

The MRI was uneventful except inside me. I struggled to hold still as I had never done before. I could feel my fingers and toes wiggle slightly as though they belonged to a different person than me. Half way through, the technician pulled me out of the tube in order to inject me with a contrast dye, and I asked him if I could please please move my hands just a tiny bit.

“As long as you don’t move your head,” he said. It was almost a relief when he pulled my hand over to the side and flexed it back and forth, tied the strip of rubber around my wrist, then slid the needle into the vein above my metacarpals.

During the second set of scans, I found myself holding my breath in order to try to stay still. When I let my breath out, I felt the air rush past my philtrum, tickling me in agonizing fashion. “Be still,” I thought, “and dream of Jean-Dominique Bauby.” It might cause some people panic to think of something like locked-in syndrome when inside an MRI machine, but the experience inevitably makes me think about what I would do if I couldn’t move forever. I try to think about the centrality of my mind to the life I live. I wonder about staying in my mind forever.

Finally, the technician extracted me from the machine. Even after just an hour, I was stiff and took a few minutes to shift around and stand up. I was very happy to get into my regular clothes and walk down the hall and out into the now waning sunshine and to drive home to my dinner.

It wasn’t until midnight that I fully realized the barista had given me caffeinated coffee. In typical fashion, I simply couldn’t unwind and get drowsy. I was tired, exhausted even, from the hour of assaultive noise in the machine and the long day of now-distant work before that. I had watched mind-numbingly dumb TV for two hours, and I expected to sail away into slumber readily. The past three weeks had been some of my best sleep nights in several years. All the work that my husband and I had been doing to help me sleep had been working.

But, no. I tossed, I turned, I played game after game of Scrabble on the iPhone. I turned the phone off and counted backwards from a thousand. I got down to one and started back up, trying to count by threes so some concentration would be required. Bruce sighed and turned over again.

Then it hit me.

“The bastard,” I said out loud.

“Wha?” Bruce roused from his sleep briefly.

“That bastard gave me caffeinated coffee!”

Eventually I got out of bed, took a Tylenol PM, went to the spare bed on the other side of the house so I wouldn’t disturb Bruce any further, cursing the Austin coffee man in one fluid tirade. I felt almost as though I’d been slipped a mickey or doped with rufies.

I gave up caffeine years ago during graduate school because I noticed not only that it kept me from sleeping well, but that it made me irritable and easily annoyed. It made me say things I didn’t mean or that I shouldn’t have said even when I had thought them. Once, at the over-caffeinated end of a long semester, I told a fellow grad student that I hoped I never had another class with her. She’d been characterized by snide asides and had given the most idiotic presentation I’d ever heard in a graduate seminar, but there was no point in me being mean to her. Later, I apologized, but I knew in the immediate aftermath that I had to give up the drug.

All these years later, I wonder if anyone could devise a study that would look into the social cost of caffeine. Sometimes I’m so astounded by the rampant aggression around me—that anger that seems to be bubbling right under the surface so much of the time—that I feel the only rational explanation is that caffeine is making everyone crazy. I think about the Romans and their lead pipes and cooking vessels perhaps being a contributing factor to the downfall of their civilization. While the lead poisoning theory remains unproven and under continuing investigation, I can’t help but think sometimes that I am caught in the midst of a decline in our society that seems to have some chemical basis.

One report in the Washington Times notes that “the rise of coffee parallels the rise of the Internet” and that because of our increasingly connected world and the demands of “economic turmoil in a hypercompetitive global economy,” we “need caffeine… more than ever.” It also notes the increasing concerns about the use of caffeine (usually in the form of soda or energy drinks) in children and adolescents.

What studies show—and, I might add, what just makes sense—is that the combination of this stressful world and the biochemical effects of caffeine is preventing people from getting the sleep they need to be effective and is irritating the heck out of people.

We don’t usually factor in caffeine’s effects when we track causes for auto accidents, though at least one driver recently claimed “caffeine psychosis” for his running over several people. There’s even a growing sense that using a little caffeine to make driving home after drinking a little safer relies on a dangerous myth: drunkenness is simply combined with inappropriate bravado rather than alertness. One trucker comments on Life As a Trucker about “the adverse effects of sleep deprivation and excess intake of caffeine” contributing to road rage. One attorney’s webpage notes that even without alcohol some caffeine-induced symptoms can “dramatically increase the likelihood that a driver will operate his or her vehicle in an aggressive manner or succumb to road rage.”

We don’t factor in caffeine the way we do alcohol and crack when people are arrested for violent crimes. While I agree with the author of this editorial published in the University of South Carolina’s student newspaper—that caffeine intoxication should not usually offer a good insanity defense in criminal cases—the fact that a few people are claiming it indicates that it’s becoming more believable. Most of the cases in which caffeine is correlated with behavioral problems seem to involve the combination of alcohol and caffeine found in some energy drinks and in “monk’s juice.” But in spite of pre-packaged alcoholic energy drinks being banned in 2011 by the FDA, due to numerous college-student deaths and studies that show they break down inhibitions dramatically, the ingredients to make your own are readily available and commonly used. Even energy drinks that don’t contain alcohol are beginning to be linked—in studies and in patterns noted by police forces—to risky and anti-social behavior. A handful of studies are cited on the LiveStrong page about Caffeine & Psychosis, noting that these studies do demonstrate that caffeine can exacerbate certain mental illnesses.

We certainly don’t factor in caffeine when we talk about the ridiculous and verbally violent depths to which our political rhetoric has fallen. Although there seems to be an anecdotal consensus that something has changed in the tone of our national and local politics, the evidence is frequently cited that politics has always contained its share of abuse and conflict. Certainly, as this slide show indicates, politicians have been drinking coffee regularly for quite some time. There is, however, one blog, started in 2011 and partly covering the current presidential campaign, that has been perhaps appropriately titled Caffeinated Politics.

Something else has also shifted: while awareness of caffeine’s two-sided impact, both bad and good, has become more widely understood, it has attracted its own fanatics on both sides of the issue. We have anti-caffeine crusaders and we have pro-caffeine defenders reminiscent of the temperance reformers vs. the anti-prohibitionists in the early twentieth century and creating something like the current hostile divide between Republicans and Democrats.

Let me say very plainly that I’m not a prohibitionist in terms of alcohol or caffeine. I even believe that most drugs that are illegal today should be legalized or at least decriminalized and that our funding should go to treatment of addictions rather than punishments for them. (And I am well aware that decaf coffee is not completely caffeine-free, so I am even indulging in that drug myself in a small way, as well as the occasional drink.)

But I am very tired of being mistaken for a prohibition-like fanatic when I request decaf (or, for that matter, when I don’t spend my entire evening slurping down massive quantities of alcohol). Baristas, bar tenders, and partiers have a tendency to treat me as though I offend their sensibilities. What I offend, of course, is their dedication to their drug, a clear sign of addiction.

This reverse moral opprobrium is fascinating to me. We have gone so far beyond the mentality that drugs are bad that a person who doesn’t partake of them is somehow the one labeled negatively. Although the political parallels eventually break down, there’s still a similarity to the world of extremes.

Of course, what this has to do with is the kind of phenomenon my husband fondly refers to as tribalism. We live in a time when we can’t be sure who we’re with and to what extent they are like us. Even the trivial bond becomes all important. Do you share my love of caffeinated coffee or might you betray me? It’s laughable, really, but it happens all the time.

Bruce has never been a coffee fan. He never drinks it either at home or away. When he walks into a coffee shop, he orders tea and never has to utter the dirty “decaf” word. He is also one of the calmest, most considered, most fair-minded men I know. I won’t give up my beloved decaf French roast in the privacy of my own home, but I am thinking I will adopt Bruce’s habit in the coffee shop world. As a tea-drinker, even an herbal tea-drinker, I may not be a compatriot, but I’m less likely to seem like some caffeine addict’s enemy and find myself secretly drugged.