Recycling transfer station, Gainesville, FL. Photo by BWingYZ.

I sometimes feel like the Queen of Garbage. Around our house, I’m the one who mostly deals with it. This is not the result of some plot on Bruce’s part— I am the long-term expert at dealing with kitty litter (and, to be honest, kitty vomit), and I am just far more obsessive about garbage than he is. A friend once told me that I reminded her of Andie MacDowell’s character in the film sex, lies, and videotape (directed by Steven Soderberg, 1989) who sat in her therapist’s office worrying about a barge of garbage stuck in the East River. My friend thought this comic.

My first memory of playing this role arises from my early teenage years when my old friend Sharon visited my family one summer. Sharon’s parents and my parents had played bridge together when we still toddled around with pacifiers in our mouths, and we’d stayed friends of the summer-visit variety. When Sharon saw me take a pile of newspapers down to the garage one day and add it to the considerable stash along the far wall, she asked me what was going on.

“The Boy Scouts do a drive every year to recycle the papers,” I told her. “And see here?” I showed her the extra garbage cans we kept for glass and aluminum. “We take these to the K-mart recycling dumpsters, too.”

“Your family is a bunch of fanatics!” she said. “You’re crazy!”

Thirty-five years later, I feel sure that Sharon and her family recycle, too, but even now there are a lot of people who don’t.

Bruce and I purchase a lot of stuff through the mail. Evidently everyone on our street buys a lot of stuff through the mail. As far as I can tell, I am the only one who bothers to break down boxes for recycling. The recycling people will only take the cardboard if it’s flat. We let boxes pile up in the garage for a while, and then I go out with the hunting knife I found when I bought a house years ago and cut them down. Sometimes I think about the new life I gave the once abandoned knife—that’s a kind of recycling, too.

And I spend hours trying to find homes for the stuff we don’t use. Recently I made a trip to Goodwill with a carload of household items—glass cookware we can’t use on the new induction stovetop, extra mugs that overflowed the cabinet long ago, some of the plethora of cloth book bags that we seem to pick up at every conference we attend. I was dismayed to learn that Goodwill won’t take blinds, as I had finally convinced Bruce to give up a large bamboo blind that we have no place for in the house we bought three years ago. I didn’t, however, put it on the curb. Instead, I put it back in the garage and began making a list of things we can give away or sell for cheap through Craig’s list.

I did a lot of this when Bruce and I moved into our house together. We owned two lifetimes of accumulated stuff, and we had to winnow it down. But Bruce laughed at me when I said we should do something with all the boxes. We had a lot of boxes—too many to break down for the recycling truck. Bruce was ready to put them on the curb. Instead, I posted them as “free” on Craig’s list. Bruce said no one would want them, but within an hour, I had six different people offering to come and get them. They were perfectly good boxes.

My grandmother, on the other hand, hoarded. It’s a thrifty habit. And like the genes that change our metabolisms when we try eat less to lose weight, I’m sure the saving gene once had a good purpose, too. But we live in a time of overkill not of scarcity, both with food and with stuff. It’s no wonder that obesity and hoarding both seem to be on the rampant rise these days. At least, I tell myself, I don’t hoard.

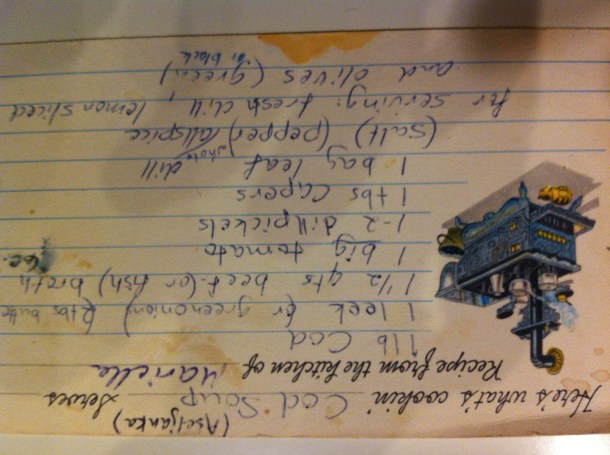

Nowadays, I take any peanuts and other plastic-y packaging stuff to our local UPS store, where they are glad to re-use them. Because they don’t pick up office paper curbside, I haul mine to campus. I’ve taken metals to a metal recycling business, and I’ve taken electronics to a business across town that supposedly re-uses parts. (It seemed to me that mostly they were in the process of smashing every part and extracting the metal, too, but at least I tried.) I take my diabetes pump supply cast-offs to the fire station in sharps containers for proper disposal of medical waste. (This is relatively easy here where there’s a fire station program, but for years I had to hunt down ways of getting my medical waste into a proper channel.) And I make frequent trips to the garbage transfer station in our area to drop off the many dead batteries that we have from my insulin pump, blood sugar meter, TV remotes, fake candles, and various computer peripherals like mice. I like the transfer station the way some people like the wrong side of the tracks—it is like a glimpse into another world entirely, with the huge, lumbering trucks and cavernous space filled with the detritus of our lives: scary and all too real.

I do other things, too, to try to be environmentally responsible. I long ago quit buying water in bottles, for instance. Bruce and I have a collection of long-lasting drink bottles, and I drink water out of the public water supply. It is the cleanest and safest in the world, after all, even if it’s not from some “pure” spring in Fiji. It was easy to make this change after I saw the water bottling plant in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, where I once lived. Bellefonte’s public water supply came from a spring, so a company bottled it and sold it as “spring water.”

Both Bruce and I—and most of the people I know—try to make choices along these lines. Most of us feel that the earth is a ticking time bomb of pollution and poison. I go to a lot of trouble, but I know it’s not enough. I often wonder if the gasoline I’m using to drive stuff around to these various places is worth it, and I’ve had my suspicions that all the stuff that gets picked up curbside is just dumped back in with the rest, a kind of p.r. stunt. I’ve known people who do a lot more than I do—one who gave up cars completely, one who left his job as a philosophy professor to join an organic farming cooperative, others who established careers related to protecting the environment or educating kids about it.

Recently, one of these latter—an old friend who works as an attorney for the EPA—lamented that she believes that recycling has become just a sop to make people feel better. I know she is right, and she made me think about what it means to be environmentally friendly. How is that term defined in a meaningful way? The EPA has, in fact, deemed the term useless in the commercial world due to a lack of clear definition.

For most of us as individuals, it’s very confusing, and I believe that most of us do only what we can see, what is simple, and what is right in front of us. I find it worthwhile to turn off the lights when I leave a room—in fact, I follow Bruce around and turn lights off after him, too. But in more complicated situations, it’s frighteningly hard to tell what’s for the best. When Bruce and I bought our house, we needed to replace miles of hideous, worn and dirty beige carpet. I did hours and hours of internet research about purveyors of wood flooring, looking for a company that had responsible environmental and labor policies. Pretty much all of them claimed they did.

We went through a similar task when we looked for our wedding rings. Mining—both metal and diamonds—is a particularly nasty business that most of us never see. But in my younger days, I’d driven around Copperhill and Ducktown, Tennessee, and I had seen first hand mining’s destruction. Though much of that land has now been reclaimed, it was denuded for better than a hundred years. I wouldn’t want to live there even now. We bought rings made from recycled metal. At least that’s what we were told. We don’t feel any ability to really know the impact of our choice.

All of this raises for me again and again what it means to be genuinely one thing or another. How do we gauge our own intentions? Do I recycle just so I can have the imprimatur of a “good person”? Do the hours I spend sorting garbage and cutting down cardboard boxes mean anything besides just another form of waste? And are my intentions what matter? No doubt they are good, but I may not demonstrate enough follow-through or commitment. Other things distract me, and my carbon footprint no doubt remains too large. At least, I tell myself, I have been doing a few things over many long years. At least I am not a Johnny-come-lately to trying to do my part.

Bruce and I were talking about this the other day, when I was contemplating to what extent I’m just a half-assed person with commitment issues. We started to generate a list of other ways in which he and I each have been unable or unwilling to “go all the way.” Some of these are not so clearly desirable as environmental sustainability and concern, but they share the expectation of purity.

Bruce and I started our list by chuckling over what I have for a long time called “macho yoga.” Just a few days ago, the New York Times featured an article about the dangers of yoga. I was glad to see them finally catching up to reality. Back in State College, Pennsylvania, during my grad school years, I classified the yoga schools and instructors in town into the “gentle” camp and the “macho” camp. My friend Mary, a returning middle-aged college student, alarmed me when she told me that after a month, her college yoga class was doing headstands. I said, “No way. You’re going to hurt yourself.” Sure enough, she herniated a disc. Yet in our town, there was a certain éclat of the macho yoga schools, and they turned up their noses at anyone else. At a party once, I had one of them tell me that I couldn’t be a true yoga devotee unless I did headstands. I already knew that I was never going to do headstands.

Bruce told me about his own discomfort with the proselytizing brand of Christianity that he was inculcated in when he was at Bible college. “I still consider myself a good Christian,” he said, “but I know a lot of people wouldn’t. For me, it’s more of an internal thing.”

Along similar lines, I have found myself uncomfortable with confrontational politics. Off and on over the years, I have made numerous attempts to advocate for candidates I believe are better than worse, to engage in canvassing, to make phone calls as elections neared, and so on. My brother has always been good at debating issues and has long been involved in local politics, but I am terrible at it. I feel that it’s necessary, but it just about gives me heart palpitations and I usually just end up making someone mad. I am much better at writing things down, and I hope that my occasional forays into issues in this blog is a genuine way that I can make a contribution, even if it isn’t protesting in the streets or knocking on doors.

Perhaps most important of all to me right now is the issue of our marriage. It took me 49 years to get married, even after a therapist told me in 1983 that I had commitment issues. Even now, happily married to a great guy, I tell myself at least once a week that it won’t last. I have learned to talk back to myself and say, “Yes, it will,” but I have a fear of disappointing both of us. I often wonder if I am a genuine wife or if I am kidding everyone including myself.

These constitute an array of issues that I feel very differently about—I want to be totally committed to my marriage, I want to be a better environmentalist, but I have accepted my low-level role in politics and I have no desire whatsoever for Bruce to become more evangelical or for me to do more strenuous yoga. Yet it was interesting to compare the ways that definitions of terms define us in each of these arenas.

This is an enormous issue in today’s political world. In an article in the upcoming February 2012 issue of Harper’s, “Killing the Competition,” Barry C. Lynn notes that the powers-that-be “have undermined our language itself” by redefining various terms. “Corporate monopoly? Let’s just call that the ‘free market.’ The political ravages of corporate power? Those could be recast as the essentially benign workings of ‘market forces.’” In another recent article, Rodolfo F. Acuña notes how euphemistic language is being used as a tool for racism. Acuña is a lightning rod in battles in Arizona over a recent law that was passed that made it illegal for “any school program to advocate the overthrow of the government, ‘promote resentment’ toward a group of people or ‘advocate ethnic solidarity.’” Like those three things are necessarily related. In other words, any kind of ethnic studies (except, of course, white) has been shut down in Arizona, where attorney general Tom Horne has re-defined many life-long Americans of color as “separatists.”

I don’t have any final answers to any of these definitional questions. The EPA is right, and we all need to look closely beyond the title of “environmentally friendly.” We all need to look closely behind all the double-speak of politics, and we all need to look at how we define ourselves.

I may not be the best environmentalist in the world, but I will still claim the title of Queen of Garbage around here, and I have every hope that my role will be valued in my life-long marriage.